What is justice? If you were to ask this question of Socrates in Plato’s Republic, it would probably take him a while to give you an answer.

Justice is a word we hear often these days. But its relevance to individuals and society is nothing new. Rather, it goes all the way back to ancient times. And back then, like now, the term was probably overused by many and understood by few.

That’s why Part I of Plato’s Republic sets out to examine justice under a microscope, so to speak.

In this most famous of his dialogues, Plato, writing in the person of Socrates, considers four distinct views of justice. Each belongs to a different member of a fictional party that Socrates and a group of his contemporaries are attending.

The occasion for the party is the festival of a moon goddess called Bendis. And the festivities are happening at the home of Cephalus, a wealthy Athenian businessman. There are many in attendance at this party, but the key figures involved in the discussion on justice are Cephalus, his son Polemarchus, a renowned rhetorician named Thrasymachus, and, of course, Socrates.

The setting of the story may be fictional, but the question it sets out to answer is real and timeless. And at the core of this question lies another, more important, question: Is happiness the product of justice or injustice?

Let’s learn about the four views of justice presented in Plato’s Republic.

View # 1: Justice is honesty in speech and action

The first view of justice in Plato’s Republic comes from the party’s host, Cephalus.

Cephalus is the eldest at the gathering. And, because of this, the honor of opening the dialogue is bestowed on him.

He begins by addressing the reason to pursue justice rather than defining it. And that reason, he explains, is the guilt that will arise during old age if one does not live a just life.

A life that is full of wrongdoing, says Cephalus, haunts the one who has done wrong and stirs him from sleep in terror.

Alternatively, a just life makes for a peaceful old age unmarred by the burden of a guilty conscience.

Therefore, a life aimed at honesty in both speech and action is most profitable. Quite simply, in the view of Cephalus, justice is defined as telling the truth and always paying your debts.

Sounds reasonable, right?

Not so fast, says Socrates.

Socrates exposes flaws in Cephalus’s definition of justice

Using his signature questioning method, Socrates exposes the flaws in Cephalus’s definition. He proposes a hypothetical to the old man that goes something like this: suppose a friend who lent you a knife were to then go insane and ask for the knife back?

In this scenario, technically speaking, you would owe a debt to your friend. And by not returning the weapon to him or telling him the reason why, you’d be acting dishonestly both in speech and action. But everyone can agree that it would be neither right to return the weapon to the insane man nor to tell him the truth about why.

And, therefore, what Cephalus calls ‘right conduct’ cannot be the complete definition of justice in itself.

So the old man concurs with Socrates that his view of justice was incomplete. And his son, Polemarchus, takes his shot at defining justice next.

View # 2: Justice is helping friends and harming enemies

Polemarchus accuses Socrates of being too literal. The young man offers his own take on the hypothetical scenario.

It goes something like this: Being just is treating your friends well, and ensuring you don’t harm them. And refusing to return your friend’s weapon, in the case that he goes insane, is helping him, not harming him, and, therefore, is the just course of action.

Socrates considers Polemarchus’s words and then restates his point: Justice, then, is any course of action that helps your friends rather than hurts them.

Yes, that’s correct, says Polemarchus.

Socrates probes further: And what about your enemies? What is the just course of action when dealing with your enemies?

Polemarchus replies that if justice means helping your friends, then it must also mean harming your enemies. So we arrive atPolemarchus’s conclusion: Justice is giving people their due, which is to help your friends and hurt your enemies.

And he wasn’t alone in this sentiment.

In fact, this was a commonly held belief in ancient Greece: “ὠφελεῖν τοὺς φίλους καὶ βλάπτειν τοὺς ἐχθροὺς;” helping your friends and hurting your enemies would ensure your own best interests, and, therefore, was considered right action.

Only Socrates would dare to challenge this maxim. And, of course, he did.

Socrates exposes flaws in Polemarchus’s definition of justice

Can it really be considered just action for one person to ever harm another?

Polemarchus certainly thinks so — as long as that person is your enemy. But Socrates illustrates the flaws of his logic in a dialectic that begins with the following analogy:

If you harm an animal — a horse or a dog, for example — are you not making it worse? Are you not making it less perfect than it was before?

Polemarchus agrees.

Then, by logical extension, if you harm a human being, are you not also making him worse off?

Yes.

And isn’t it true that the ability to comprehend justice and act justly is unique to the human race?

Yes, that’s true too, says Polemarchus. I suppose animals have no notions of justice.

Great, we’ve agreed. Now can we also agree to say that to harm a man makes him less perfect and, therefore, less just?

Yes.

And a just person cannot exercise justice by making anyone, even his enemies, less just. Correct?

Right.

The function of goodness, Socrates then concludes, has nothing to do with producing harm. So if justice is good then it can never be just to harm anyone, regardless of circumstances.

View # 3: Justice is the will of the stronger

After watching Socrates dismantle the views of both Cephalus and Polemarchus, Thrasymachus, the heavy hitter, steps up to the plate.

Thrasymachus was a well-known rhetorician and sophist in Athens during the 5th century BC.

In Plato’s Republic, he forcefully presents, perhaps, the most extreme view of what justice is.

To Thrasymachus, justice is no more than the interest and will of the stronger party. The Greek despot, therefore, is the ultimate arbiter of justice, imposing his will upon his subjects simply because he is stronger than them.

Socrates, of course, disagrees with this assessment.

Socrates exposes flaws in Thrasymachus’s definition of justice

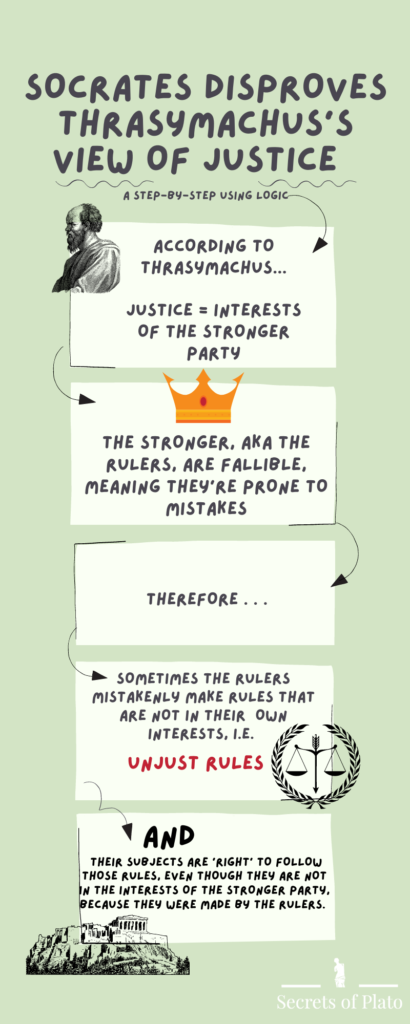

He starts by restating Thrasymachus’s argument: What’s right, or just, is whatever is in the interests of the men in power. Is that correct?

Yes, Thrasymachus confirms.

Then Socrates inquires about the character of the men in power: Are the rulers infallible?

Well, no. They’re men. Of course they’re prone to make mistakes.

So when making laws the rulers can either make them well or badly. Let’s say they make them well when they’re in their own interests, and badly when they’re not?

Sure.

Socrates then goes on to expose the conflict in Thrasymachus’s argument, thereby disproving his view of justice: If your rulers are fallible, as you agreed they are, and they are prone to making rules badly (meaning the rules are not in their own interests) and then their subjects go on to obey those rules (as they should since those subjects are doing what is ‘right’ by following the rules) then it is right to do what’s not in the interest of the stronger party.

If that was confusing, this infographic breaks it down in simpler terms:

Herein lies the logical flaw of Thrasymachus’s argument.

Thrasymachus pivots: Justice is the will of an infallible ruler

Hold on, says Thrasymachus.

The sophist begins to backtrack.

He changes his argument: Justice is still defined as the interests of the stronger party. However, as soon as the stronger mistakes his own interests he ceases to be a ruler. Therefore, as long as a ruler is acting as a ruler, he never makes mistakes and always rules in his best interest.

In other words, Thrasymachus modifies his definition of justice to be that of the interests of an infallible ruler.

Accordingly, Socrates shifts gears and begins to examine this new argument of Thrasymachus.

As always, the philosopher starts with an analogy. He refers to the ruler as practicing a craft in the same way a ship’s captain or a physician does. The interest of the captain’s craft is to navigate the ship; the interest of the physician’s is to heal the patient’s body.

Socrates makes the assertion that any craft’s interest is “its own greatest possible perfection.”

And a craft, or an art, whether it be ruling, navigating, healing, or something else entirely, “is true to its own nature as an art in the strictest sense.”

Therefore, it cannot be concerned with its own interest first and foremost: The physician doesn’t study her own interests, but rather the needs of the body; the ship’s captain cannot be practicing his craft properly unless his main concern is navigating the ship. Likewise, the ruler’s craft is concerned primarily with the welfare of his subjects.

“The art,” says Socrates, “has authority and superior power over its subject.”

So if the ruler is acting as a ruler, his primary concern can’t be his own interests, but rather those of his subjects. Otherwise, he is not acting as a ruler.

By this point, Socrates has spun Thrasymachus’s argument on its head twice over. But the sophist is still a long way off from admitting defeat.

And so we proceed to the final view of justice presented in Plato’s Republic, in which Thrasymachus asserts that injustice is more profitable than justice.

View # 4: Injustice is more profitable than justice

The fourth view of justice in Plato’s Republic would more accurately be called an approbation of injustice.

At this point, an irate Thrasymachus reveals himself as an immoralist. He advocates for abandoning the pursuit of justice altogether and makes the case that it isn’t worth it because it doesn’t lead to happiness.

He argues that all the Greek kings from Homer’s time onward have practiced injustice and have been universally admired for it. Therefore, they must be the happiest men, which proves that injustice is ‘right’. And such a noble pursuit as being just, he concludes, isn’t profitable.

In a tirade about the realities of justice and power, Thrasymachus makes the following points:

1. At its core, the pursuit of justice appeals to cowards: “When people denounce injustice, it is because they are afraid of suffering wrong, not of doing it.”

2. A ruler is like a shepherd. He is only concerned with the welfare of his sheep insofar as he can profit from exploiting them.

3. The just person always ends up with the short end of the stick.

Socrates responds: Injustice is not more profitable than justice

Socrates returns to Thrasymachus’s analogy of the ruler as a shepherd.

He relates it back to the proof established in view # 3, that each art has superior power over its subject. And so it holds that the primary concern of the art of shepherding is to ensure the well-being of the flock. Doing so is most profitable for the shepherd because the welfare of the sheep provides for the welfare of the shepherd.

In his view, this supports that injustice is not more profitable than its opposite.

Socrates shares his view of justice as it relates to happiness in Plato’s Republic

Now that each view of justice in Plato’s Republic has been declared and debated, Socrates shares his own view on the matter. And he is particularly interested in justice as it relates to happiness. And even more so in the element that he says links the two together: virtue.

Socrates claims that in order to live a just life, one must be virtuous. And that’s because the virtue of the soul is justice.

How is this so? Well, it requires one to make the leap into the realm of metaphysics.

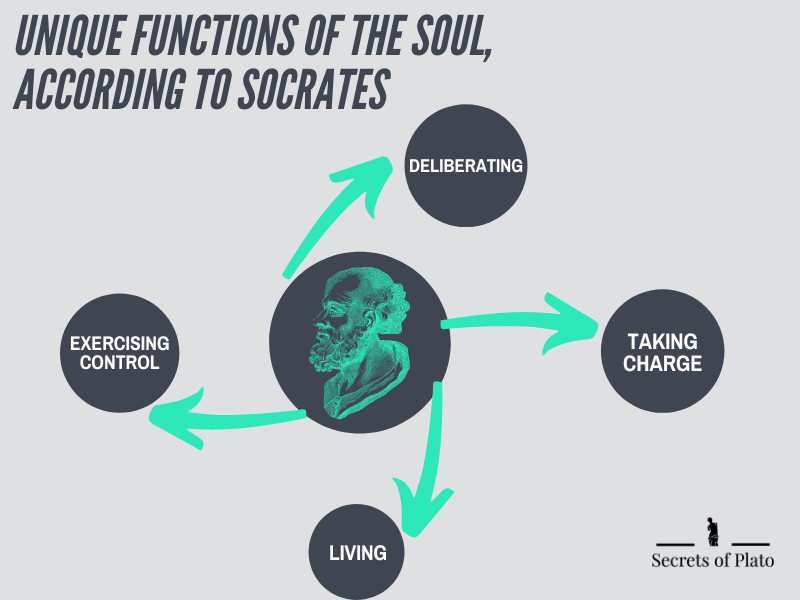

But it has everything to do with what Socrates calls the unique functions, or virtues, of the human soul. These are deliberating, taking charge, exercising restraint and control, and, above all, living.

And these specific virtues of the soul are the faculties that are required to be just.

Think about it. In a situation that requires you to be the arbiter of justice, you’d need the faculties to deliberate on the issue at hand, take charge of the situation if required, and exercise control if not.

Now how does virtue relate to happiness?

First off, Socrates’s definition of happiness is much more dynamic than the shallow one promoted in our modern culture. He calls happiness the internal order and unity, which makes for a global sense of welfare and well-being. And, therefore, happiness is an indication that the human soul is in its optimal condition.

So it holds that if certain conduct is defined as virtuous — deliberating, taking charge, exercising control — that conduct brings the soul to its most perfect state. And in that state, the soul will be aligned with an overall sense of welfare and well-being, which is happiness.

Therefore, virtue = living well = happiness; or, better yet, virtue = happiness.

Socrates concludes that justice is a principle of that internal order and unity which virtue and happiness produce.

To the contrary, the immoralist, the unjust person, is internally at odds with himself. His injustice will result in unhappiness because he lacks virtue.

If our definitions of virtue and happiness are not the same, then one is incorrect. And so, according to Socrates, one cannot attain happiness without virtue.

Happiness, therefore, is the product of justice.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.