The Roman Republic was born out of a rejection of monarchy.

Since the Republic’s foundation in 509 BC, no word was hated in Rome as much as “rex” (king). The Roman historian Livy recounts the remarkable foundation myth that explained the overthrow of the old monarchy: Roman nobility avenged the King’s rape of a virtuous Roman matron by driving the royal family into exile and instituting a Republic. This new form of government was conceptualized as a “res publica,” a public matter.

The historicity of the story is dubious, but its meaning is clear: Kings are debauched corrupters of virtue. Kingship equates to tyranny. The ideology of the new Republic had no room for a sole ruler.

The Roman Republic and Its Rejection of Monarchy

The new Republican government was an oligarchy in which power was controlled through a

system of checks and balances. This system and the institutions that administered it became central to the Romans’ political identity. As the Republic expanded through the Italian Peninsula, and later through the lands of the eastern and western Mediterranean, the system of government that had been established in 509 B.C.E. remained. Expansion put a heavy strain on the old system by the first century BC.

Yet even as social pressures grew, and even as powerful men distorted the institutions of government to serve their own ends, the Senatus Populusque Romanus (the Roman Senate and People, abbreviated S.P.Q.R.) was publicly acknowledged as the source of Rome’s power. The dictator Sulla wielded sole power for a brief period, but in the form of a legitimate constitutional exception, not as an alternative to republican government. The glorification of the Republic long outlived the Republic itself. Indeed, S.P.Q.R. continued to appear in inscriptions, coins, and literature long after the functioning republic ceased to exist.

In 48 BC, Julius Caesar defeated his rival Pompey. He then attempted to gather sole power in Rome, testing the waters to see how many honors he could accept, and (probably reluctantly) declining a crown. Julius Caesar masterfully subverted the institutions of government to achieve his own ends and to secure his own power, but he could not reign as a monarch. In 46 BC, he accepted instead the title of dictator, which was a legitimate office (though it was meant to be of limited duration, and Julius Caesar held it for the rest of his life.) Five hundred years after its inception, even as the Republic degraded and finally collapsed under the weight of social discord and powerful dynasts, the fiction of the Republic remained sacrosanct. Indeed, Julius Caesar’s biographer Suetonius concluded that in spite of all Caesar’s many achievements, his desire to be King justified his murder.

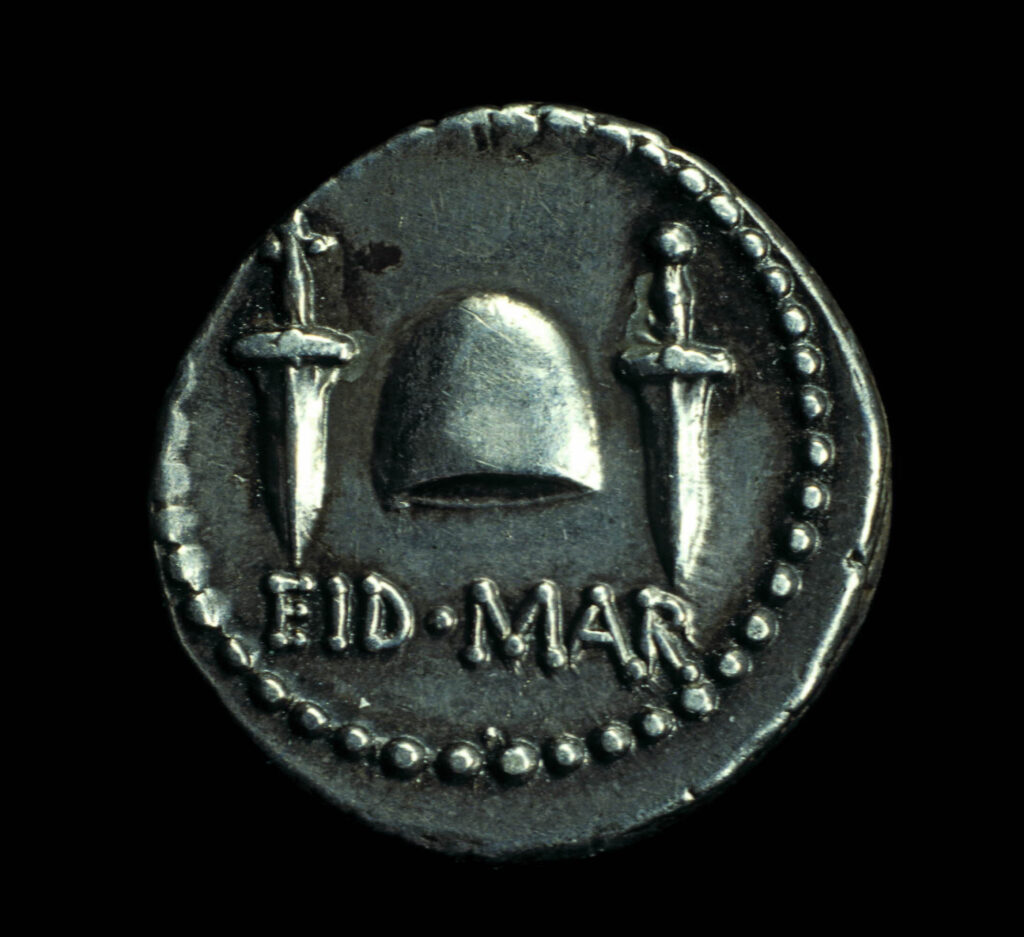

With that assessment, however, the people of Rome disagreed. On the Ides of March in 44

B.C.E., Julius Caesar’s assassination by a conspiracy in the Senate plunged Rome into war.

Under pressure from the Roman people, the Senate posthumously deified Julius Caesar.

Caesar Augustus, Son of a God

Julius Caesar’s assassination ushered in a bloody civil war that was ultimately won by his

nephew and adopted son, Octavian, later known as Caesar Augustus. Octavian’s victory over Marc Antony and Cleopatra gave him immense power and renown in Rome, which he used to shape virtually every dimension of Roman life. Slowly, quietly, and behind the scenes, Octavian would transform Rome into an Empire. This transformation was a delicate process that required both careful political manipulation and extreme sensitivity toward the Roman cultural rejection of monarchy.

Octavian could not openly claim the legal authority of a monarchy, so he developed instead a moral authority to rule. In the Roman context, this moral authority was perhaps the more

powerful tool. It stemmed from his association with Julius Caesar, and so this association formed the core of his early propaganda. He amplified the association in coinage minted throughout his reign. Octavian would utilize many forms of propaganda to develop his political authority and to build his image as Rome’s greatest patron and benefactor, including public works, statuary, architecture, and literature. However, coinage reached the widest audience, and Octavian continued his adoptive father’s radical innovation of putting his own portrait on currency. In 38 BC, a coin struck in Italy depicted his portrait as Caesar, Son of the Divine, on the obverse, with the divinized Julius Caesar on the reverse.

Octavian also utilized other powerful images like that of the Sidus Iulium, the ‘Julian star,’ which represented the comet that shone after Julius Caesar’s assassination. This heavenly apparition was believed to represent Julius Caesar deified. The association on coins of Octavian and the Julian star cemented in the popular imagination Octavian’s connection to Julius Caesar and emphasized his divine origin.

Caesar Augustus and His Political Power

The choice of which formal offices to hold was a delicate one. Octavian wanted to avoid his

adoptive father’s mistake in accepting too many offices and honors. He judiciously considered which titles to accept and which to decline, choosing not to accept a consulship for life. It was of paramount importance that any power he exercised seemed to be in keeping with the traditions and institutions of the Republic. In 28 BC, a coin depicts him on the obverse, with the inscription IMP[erator] Caesar divi F[ilius], and on the reverse, depicting him as a citizen magistrate restoring the laws and rights of Rome.

In 27 BC, Octavian declared power returned to the Senate. In return, the Senate conferred upon him the title of “Augustus,” or “revered one”.

“Augustus” was an honorary title, not a political one, but it was nonetheless a powerful

acknowledgement of his moral authority. The Senate also granted Octavian–now Augustus–proconsular governance of the provinces of the Empire, including those in which most troops were stationed. Spain, Gaul, and Syria became imperial provinces, governed by legates that Augustus himself selected. Egypt would be considered Augustus’s private domain, and his discretion in administering Egypt’s finances allowed him to fund massive public projects and to present them as gifts to the people of Rome.

Augustus remained careful—more careful than his adoptive father had been—about the number of offices he held. In 23 BCE, he declined the consulship, but this was not a detriment to his power. In addition to the power he now wielded over the army by virtue of his proconsular rule in the provinces, the Senate also voted him the powers, but not the office, of tribune. The tribunician power was immense, conferring among other things the right to submit legislation and the right to veto. This vastly expanded his legal power, while still allowing him to avoid the censure that fell on Julius Caesar for holding more offices and honors than a Roman should. Augustus preferred the title of princeps, or “first man,” which designated him as the first among the citizens. Caesar Augustus saw to it that his power, though radical and unusual, was constitutionally justifiable, allowing him to claim at the end of his life, “I excelled all others in dignity, but of power I held no more than those who were my colleagues in any magistracy.” (Deeds of the Divine Augustus, 34)

Caesar Augustus and the Propaganda of Moral Authority

The Roman reverence for tradition had created, over time, a tense relationship between the

Roman past and the need for innovation. Reverence for the customs of the elders (mos maiorum) was a fundamental characteristic of Roman culture. Caesar Augustus had unique propagandistic needs: he had to build a public image of traditionalism and championship of the “mos maiorum” while also promoting his family as the best and most natural rulers of Rome. Therefore, he rebuilt temples. He introduced legislation to limit divorce and to punish adultery. He lived well but modestly, avoiding ostentatious displays of personal wealth. His wife, Livia, was upheld as the ideal Roman matron. When members of the imperial family failed to uphold this image, they paid a steep price. Augustus exiled his own daughter Julia when she violated the honor of his household through her adulterous relationships.

Caesar Augustus’s propaganda of the family was also the key to solving his most perplexing problem: how to ensure succession in a monarchy that did not actually exist. Perhaps the most famous example of the promotion of his family in art is found on the Ara Pacis.

Consecrated in 9 BCE and celebrating Augustus’s return from Gaul, the iconography of the altar mixes Roman tradition and myth with Augustan propaganda. Many of the panels depict traditional religious images, including animals led for sacrifice. The images invoke a prosperous and peaceful Rome. Amidst the altar’s iconography is also a depiction of the family of Augustus. Importantly (and unusually), the children of his family are also depicted.

Augustus’s presentation of his family as champions of Roman values was a necessary element in his goal to ensure succession. There could be no overt succession plan, because there was no overt monarchy. But the suggestion could be planted, and nurtured, that the Augustan family was the natural and right source of power for Rome.

Caesar Augustus is recognized now as the first emperor of Rome, though the growth of his power was gradual. It is difficult to know when, and how, the people of Rome came to understand that the age of Republic had passed. Caesar Augustus’s reforms led to a long period of relative stability for the Empire known as the Pax Romana, or Roman peace. It also marked the closure of an age in which ordinary citizens played a strong role in choosing leaders or passing laws through their votes in the assemblies. In Rome’s new political reality, these decisions would shift to the Emperor. The sphere of communication between government and citizen moved to the games and public gatherings, in which the Emperor was recognized as the central political authority.

Caesar Augustus transformed Rome into a monarchy without destroying the illusion of the Republic. By the end of his long reign, power had naturally aligned with his family. His propaganda of traditionalism allowed him to reinvent a monarchy without admitting the end of the Republic.