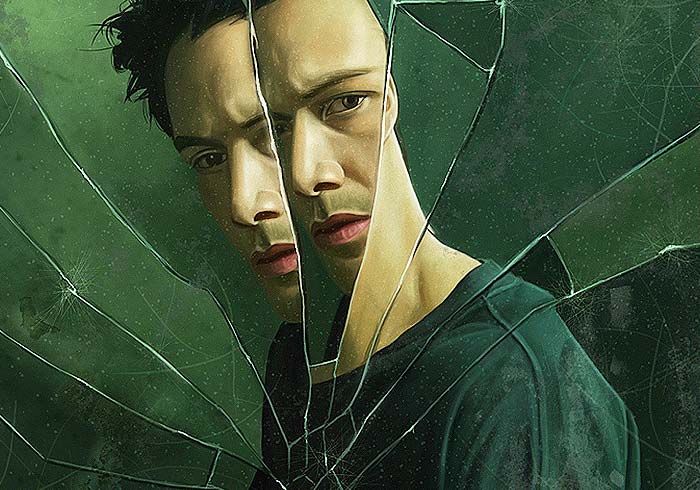

Plato’s allegory of the cave challenges readers to reconsider their understanding of reality. Its main point is simple: The things that you believe to be real are actually an illusion. True reality, if one can use that phrase, is beyond the apprehension of your senses. In this way, you could say the allegory of the cave is like the ancient world’s version of the The Matrix.

It informs readers that there’s something more real (and more beautiful) beyond that which we perceive with our senses here and now.

In Plato’s words, this true reality is “knowledge of the Good,” to which the vast majority of humans are oblivious. And the cave serves as a simple illustration for humanity’s current condition on its path toward enlightenment.

Let’s review Plato’s cave allegory in detail.

Plato’s cave allegory: Prisoners and puppet masters

Imagine, if you will, a chamber beneath the ground in which a group of men are held as captives. These men have chains around their legs that hold their bodies in place, as well as chains around their necks to prevent them from rotating their heads. All they can do is stare directly forward at a wall on which shadows move this way and that.

These are the cave dwellers.

They’ve been in shackles like this since childhood, and so they don’t even know they’re prisoners. Their only notions of reality are the shadows that pass on the wall before them.

Behind these prisoners are the puppet masters, the ones who broadcast images onto the wall. And behind the puppet masters is a fire that illuminates the room and creates the shadows.

Outside the chamber where the cave dwellers and puppet masters reside is a long corridor that leads to the cave’s opening. Here, only a faint stream of light filters in from the outside world.

Sounds like a strange scenario on its face, right?

Remember Plato’s Cave is an allegory, which means everything represents a concept, an ideal, or a principle. And the concepts being investigated here are the four states of human cognition, which are intelligence, thinking, belief, and imagining.

The shackled cave dwellers, for example, represent humankind’s lowest form of cognition, which Plato calls imagining. This is a state that accepts images and other sense perceived things wholly as reality. And, for this reason, it’s an unenlightened state.

Escape from the Cave: Moving toward enlightenment

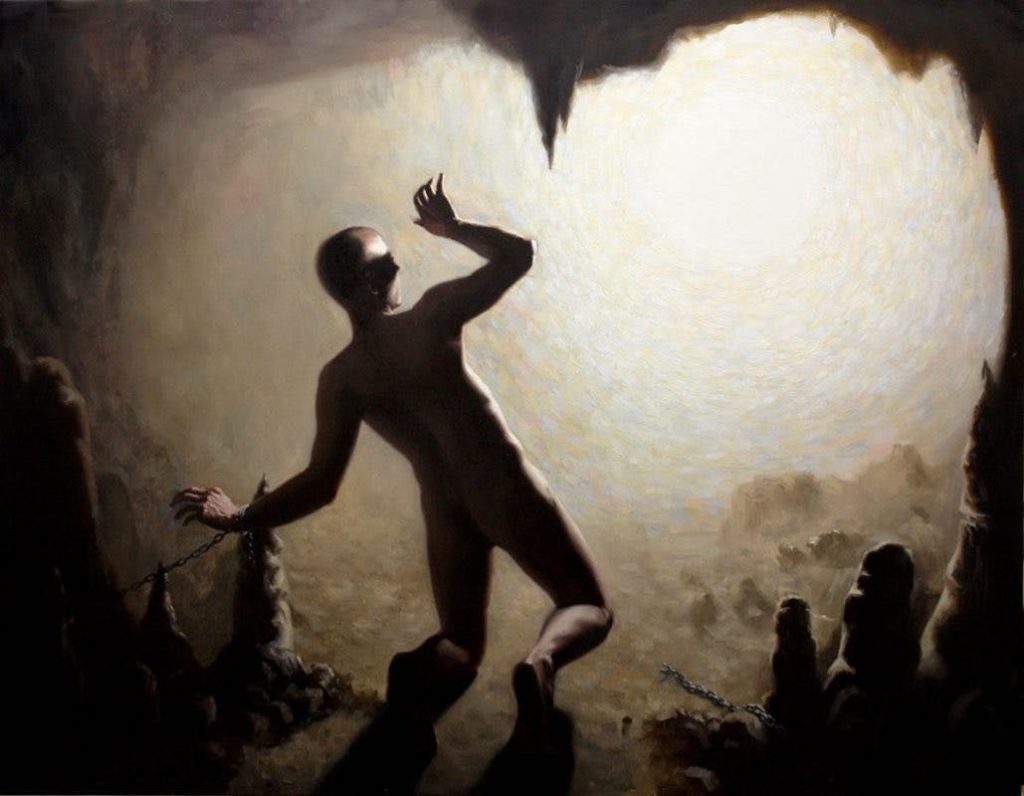

Now suppose one of these cave dwellers were to somehow break free of his chains.

His body would ache and his eyes would be strained when looking at the fire. If he were to make it to the cave’s entrance, the light flooding in from the outside would blind him. And, to make things worse, he’d be perplexed by all the new forms he would come to see. After all, he would have spent his whole life until now believing that the shadows on the wall were real. And so he’d cling to them and doubt the existence of all these other forms.

This is akin to the process of encountering true knowledge, of moving toward enlightenment, according to Plato.

The story continues: the escapee would need time to adjust before being able to see the things in the upper world. Similarly, the process of learning and acquiring knowledge requires time.

First he would be able to see shadows. After that, the different forms of the earth would become visible. And then, images of other human beings. Finally, the escapee would be able to see the Sun, the brightest object in the upper world.

He would eventually grow so accustomed to the upper world that he would be able to study the Sun’s nature.

The Sun as Goodness in the Allegory of the Cave

In Plato’s cave allegory, this passage of breaking free and adjusting to the light of the world is about the process of moving from ignorance to knowledge. Its meaning is that it takes time to travel from a state of imagining to intelligence — the only true form of knowledge.

The Sun in the upper world represents goodness, which gives light and existence to everything else. It’s seen last because, as Plato writes, “the last thing to be perceived and only with great difficulty is the essential Form of Goodness.” And so only with the comprehension of goodness can one attain real intelligence.

Return to the Cave

We now come to the last part of Plato’s cave allegory, in which the former cave dweller is a free man living in the upper world.

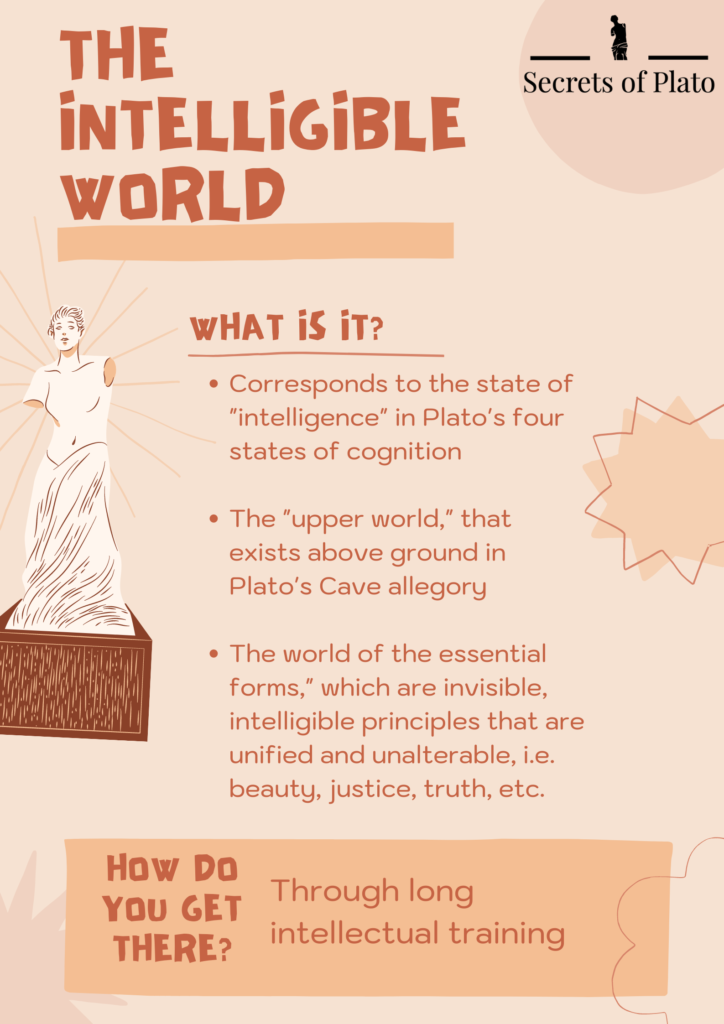

This upper world represents what Plato would call the intelligible world, or the world of essential forms in which things exist in their perfect, unalterable forms. To the contrary, the cave is the sense perceived world. It represents the place that we humans live and transact in, mistaking shadows for reality.

And so Plato beckons us to consider what would happen if the free man were to leave the upper world and return to the cave to resume his former life. How would he readjust? How would his fellow cave dwellers receive him?

The answer is that his eyes would be filled with darkness. He would be compelled by the other cave dwellers to comment on the shadows as if they were real. He’d be jeered at for leaving: They’d say it wasn’t worth the trouble since all it resulted in was his vision becoming impaired.

If he attempted to emancipate them from their chains, they’d kill him.

Application of the allegory of the cave

So, what is the practical application of Plato’s cave allegory?

In other words, why spend time learning about it?

For Plato, in his quest to describe the ideal state, the allegory of the cave illustrates the dilemma of leadership. That is, you want your leaders to be people that have ascertained knowledge of the “upper world,” or essential forms. But, in order to do so, they would have had to have made the journey out of the cave and into the light, so to speak. And it’s entirely reasonable — even likely — that once they’ve apprehended knowledge of the intelligible world, they won’t want to return to transact in the cave and rule over the cave dwellers.

In Plato’s words, “it is no wonder if those who have reached this height are reluctant to manage the affairs of men.”

The point is, those who have put in the time for intellectual training, and, consequently, have reached a state of intelligence, i.e., the very people you would want to govern the state, most often would rather refrain from ruling.

Why discuss the shadow of justice in the cave, for example, when you’ve seen the essential form of justice in the upper world?

Because, he goes on, “the life of true philosophy is the only one that looks down upon offices of state.”

The dynamic that Plato’s cave allegory illustrates explains why leadership roles so often fall into the wrong hands.

I am an Amazon affiliate. I earn a small commission when visitors to my site click on one of my links and make a purchase. There is no extra cost to the buyer. Certain links may be affiliate links.