Democracy is, perhaps, the greatest invention of ancient Greece. Its meaning — quite literally, power to the people — has become the mantra of just societies the world over. But in Plato’s philosophy, democracy is simply another political system, and one that’s worthy of criticism at that. In The Republic, our favorite philosopher dedicates an entire chapter to the views of Socrates on democracy.

And, you might be surprised to learn, they’re mostly negative.

In fact, Socrates was wary of democracy — a far cry from being its supporter. His outlook was fueled by the belief that states should be governed by philosopher kings. These are men who have attained knowledge of the world of essential forms after long intellectual training. And, therefore, his faith in the political judgments and character of everyday Athenians is limited, to say the least.

Let’s learn about the views of Socrates on democracy in Plato’s Republic.

Socrates on Democracy: Historical Context

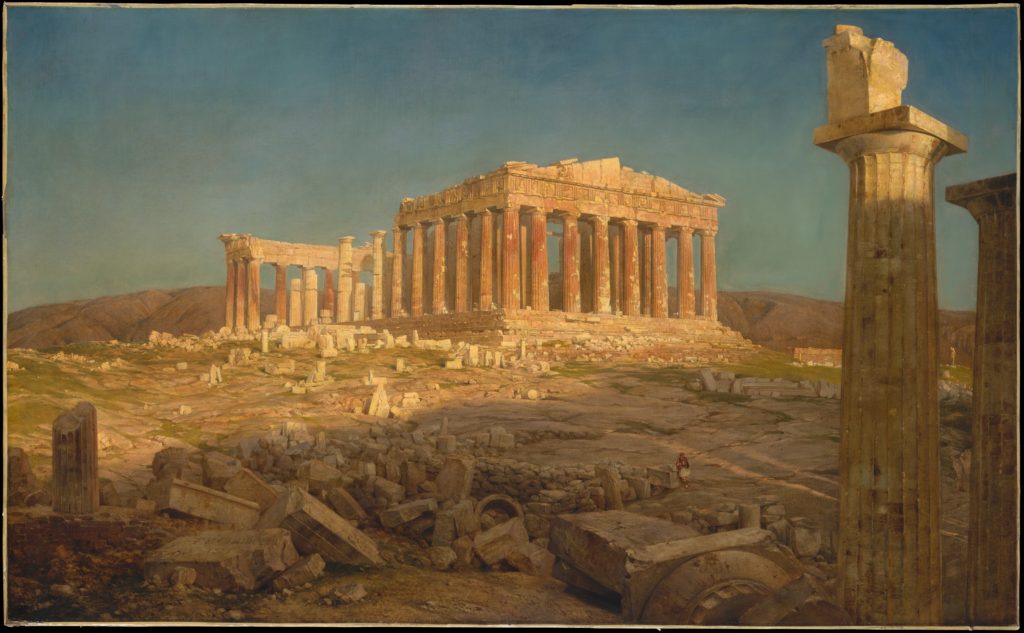

The views of Socrates on democracy were formed at least in part by his personal experience living in one. After all, much of Socrates’s life unfolded in that period of prosperity called the Athenian Golden Age.

For almost fifty years, the ancient city of Athens experienced a reprieve from wars with its neighbors. And the resulting peace ushered in advancements in the arts and philosophy, and, most notably, the heyday of Athenian democracy.

It’s important to note, however, that ancient Athenian democracy wasn’t the same as today’s liberal democracy. The former was a direct democracy, i.e. one in which citizens participated in government without elected representatives as go-betweens.

Therefore, the views of Socrates on democracy are not an indictment of the types of political systems we live under now. Rather, he’s talking about democracy in its purest form. One in which every qualified citizen takes equal part in governing the state.

So, what did Athenian democracy look like?

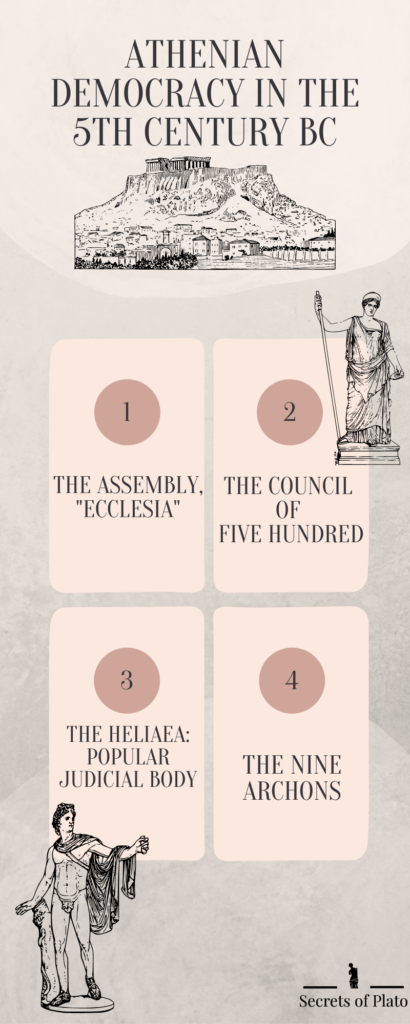

Here’s a simplified overview of how Athenian democracy worked in the 5th century BC:

The Assembly, called “Ecclesia” in ancient Greek, was the central governing body in ancient Athens. It was responsible for electing generals and magistrates and it had final say on legislation. The Assembly was open to all qualified adult male citizens: this meant Athenian men over 18 who had completed their compulsory military service of two years. At least 6,000 members were required to be present at the Assembly for legislation to pass.

The Council of Five Hundred was responsible for carrying out the business of the Assembly, which also appointed its members.

The Heliaea was a judicial body composed of every eligible (read: male) citizen over 30 who had taken an oath to uphold the Athenian constitution.

Finally, the Nine Archons were the city executives. These elected officials assumed various ceremonial, religious, and political functions. Notably, they certified the members of the Heliaea.

What about the role of women in Athenian democracy?

If you’ve been wondering what about the women?, know that gender inequality was endemic to Athenian institutions. Unfortunately, women had no voice or representation during the Classical Period of Greece. In The Republic, however, Plato makes a case for the equality of women.

This is all just to provide some historical background related to the views of Socrates on democracy. Now, let’s hear about his objections to the system itself.

Socrates on Democracy & “The Democratic Man”

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates claims that democracy is always the outgrowth of a failed oligarchy. But, whereas the primary motivation of the oligarchy is to gain wealth, democracy arises when “the poor win.” Its aims are to banish the luxurious state and ensure liberty for all. But this liberty can often lead to undisciplined pleasure-seeking on the part of its citizens.

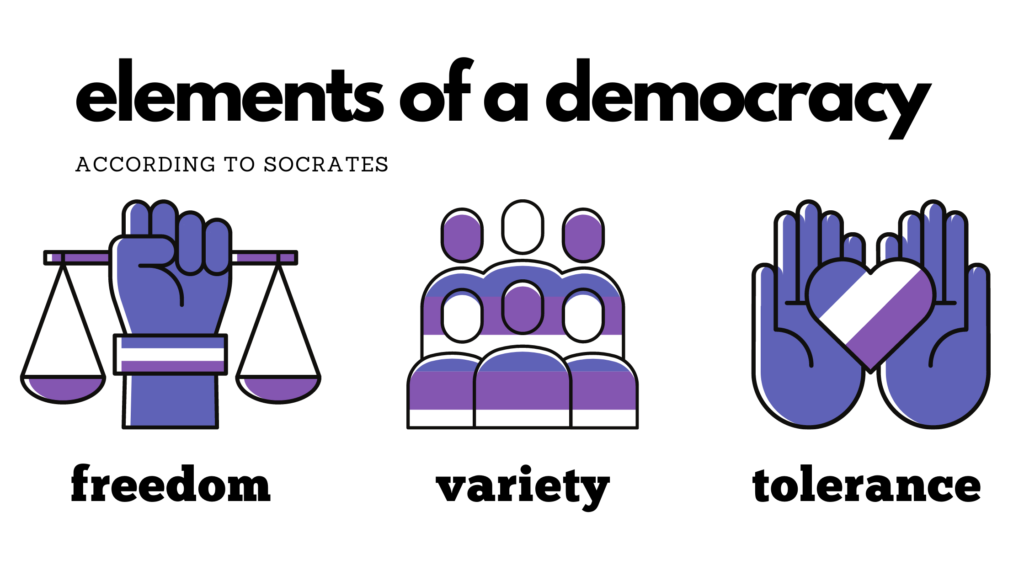

He elaborates on the key elements of a democracy, which are:

1. Freedom: Citizens do as they please; freedom of speech is integral.

2. Variety: No one is forced to do anything. And, as a result, citizens assume whatever functions they please, which results in a society marked by enormous variety.

3. Tolerance: The two prior characteristics give birth to a broad tolerance that doesn’t exist under other systems.

Then Socrates explains how these elements, which sound nice, are actually negative for the society because of their corrupting influence on the individual. He does so by introducing us to the “democratic man,” one whose “life is subject to no order or restraint.” This democratic man illustrates the perverse nature of democracy.

Because of the freedom and resulting variety afforded him by his society, the democratic man lacks discipline. He never learns to tame, what Socrates calls, “unnecessary appetites,” i.e. those worldly pleasures that rot our souls.

The democratic man does as he pleases whenever he pleases and seeks a “pleasant, free, and happy” life above all else. In this pursuit, he falls prey to “drones,” or men who are under the influence of excess and prodigality. The result of his pleasure-seeking is internal disorder.

Through his description of the democratic man, we come to understand that Socrates sees democracy as a sort of controlled anarchy. He believes that the lack of discipline and “early learning” about the importance of subduing unnecessary appetites — something that’s characteristic of democracy — leads to the spoiling of the individual, and, by extension, the decay of society.

Analysis of Plato’s Philosophy: Socrates on Democracy in The Republic

The character of Socrates in Plato’s Republic is concerned, above all else, with the relationship between the internal health of the individual and that of the state. He believes that the internal order of the individual has bearing on the greater society. And for an individual to maintain this so-called internal order, he or she must be disciplined and virtuous. So it’s no wonder that a system that encourages unfettered freedoms without demanding order and discipline from its citizens would be suspect to him.

In his description of the ideal state, Socrates sets out a society in which order and virtue are central. Everyone has a role to fulfill, and at the helm of the government is a philosopher king who has proven himself to be most virtuous, and, therefore, best fit to rule.

Democracy is the complete opposite of this vision by its very nature. And so it makes sense that Socrates was one of its biggest critics.

I am an Amazon affiliate. I earn a small commission when visitors click on one of my links to make a purchase. There is no extra cost to the buyer. Certain links may be affiliate links.