The three periods of ancient Greece produced countless famous names: Aristotle, Homer, Pythagoras, Leonidas, Cleopatra, Euclid, Socrates, Alexander the Great.

Plato, this website’s namesake, is just one more out of so many that most modern people can identify.

The one thing that all these names have in common is that each was a product of the ancient Greek world – a world that spanned almost 1,000 years and thrived on three separate continents. And within that time and space, historians have demarcated three periods of ancient Greece. Each was unique in its own way, but collectively they were characterized by war, colonization, philosophy, democracy, tyranny, beauty, empire, and so much more.

In this article, we’ll review the three periods of ancient Greece: The Archaic Period, the Classical Period, and the Hellenistic Period. We’ll outline their dates, discuss what they’re best known for, and highlight the most famous historical figures to arise from each of them.

The Archaic Period (~800 BC – 480 BC)

Around 1,200 BC, an epoch of discord and upheaval known as the Late Bronze Age Collapse rocked the civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean. This epoch saw the demise of the Mycenaean Greek culture, the beginning of the end of Pharaonic Egypt, and the total and utter destruction of the Hittite Empire. The culprits behind these events were the so-called Sea Peoples: A confederation of marauding warriors from the northern Aegean who ushered in the Greek Dark Ages.

Fast forward 400 years and we arrive at the beginning of the Archaic Period. This is the first of three periods of ancient Greece, and the one in which we see glimmers of light emerging from those dark ages.

The Archaic Period was a time of discovery, trade, settlement, and colonization.

Exploration & Colonization

Adventurous Greeks set sail from their poleis on the mainland or in the Cyclades to explore both the western Mediterranean basin and the Black Sea. They founded cities like Marseille and Nice in southern France. But, most notably, they settled and significantly developed southern Italy and Sicily, which went on to be called Magna Graecia.

The ancient Greek colonies in Magna Graecia were prolific. Sybaris and Croton are among the most famous in southern Italy. Syracuse, perhaps the most important, and Agrigento in Sicily are still home to ancient Greek ruins. Each new settlement, or polis, was connected to a “mother city,” or metropolis, on mainland Greece.

In addition to settlements, Greeks of the Archaic Period established emporia, or trading posts, all over the Mediterranean, but most densely in Magna Graecia.

From the island of Ischia, off modern-day Naples, for example, Euboean Greeks traded with Etruscans, the pre-Roman civilization that dominated mainland Italy.

They also maintained emporia in Sardinia (where they interacted with the native Nuragic peoples), Corsica, and some parts of coastal Spain.

Greco-Punic relations during the Archaic Period

During the Archaic Period of ancient Greece, the global superpower of the day were the Phoenicians. This seafaring empire was born out of several prosperous city-states that bejeweled the coast of the Levant in modern-day Lebanon.

Their knack for trade and exploration led them to discover lands as far west as southern Spain and the Atlantic coast of Morocco. And, soon enough, a Phoenician city called Carthage would rise to dominate the western Mediterranean and create an empire of its own.

Before the Romans even existed, Phoenicians largely controlled the Mediterranean world. And this can be said for the entirety of the Archaic Period of ancient Greece.

Greeks from this period had significant interactions with Phoenicians. They traded with them. But they also fought, mostly on the island of Sicily.

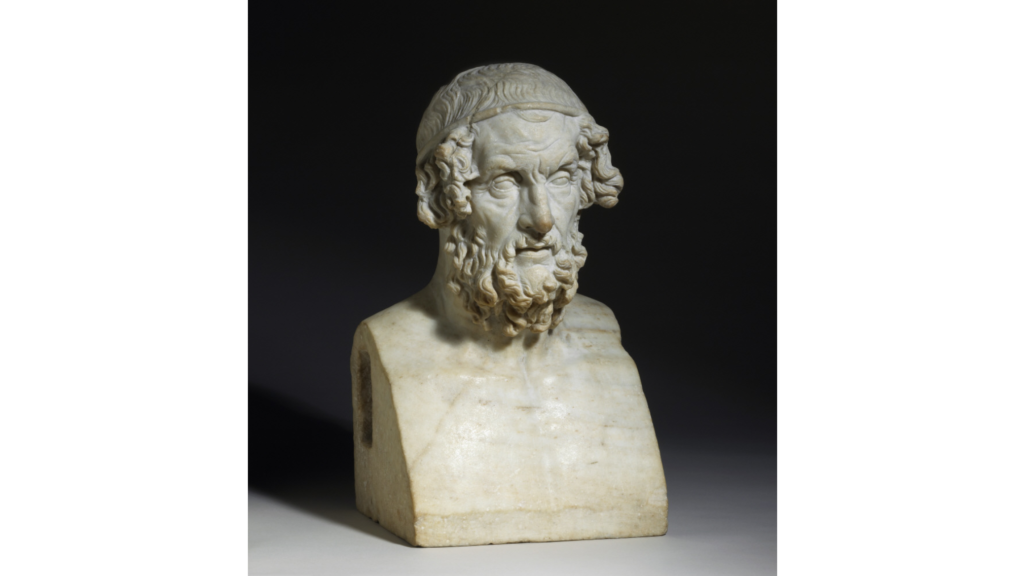

Famous Greeks from the Archaic Period: Homer

Homer is perhaps the most famous name to come out of the three periods of ancient Greece collectively, but most definitely from the Archaic Period.

Whether or not he was actually a real person is another matter entirely.

But we can be certain that the works attributed to Homer came into being during the Archaic Period. These are, most notably, the epic poems of the Iliad and Odyssey.

These stories detail the Trojan War and the fantastic journey home of one Odysseus Laertes, king of Ithaca, after its conclusion. Both epics were critical in forming the Greek identity that remained in tact throughout all three periods of ancient Greece.

Homer brought to life for the first time the mythical gods and goddesses of the Greek pantheon. And his impact on Western Civilization was so significant that his works are still required reading in many schools and universities worldwide.

Pythagoras

If you’ve ever taken a basic math course, you’ve at least heard of Pythagoras. After all, he lends his name to the Pythagorean Theorem, which postulates a formula for obtaining the value of the sides of a right triangle.

And if that sounds boring to you, don’t give up on him yet. Pythagoras believed that there was a connection between mathematics and the divine.

His mystic philosophy, such as divine numbers, heavily influenced Socrates and Plato, and, by extension, all of Western Philosophy. He was born in Samos, an Ionian Greek island off the coast of modern-day Turkey, toward the very end of the Archaic Period. However, Pythagoras spent much of his life and ministry in Magna Graecia, specifically in Croton, where his teachings were studied widely.

Some of the principal tenets of Pythagoreanism were:

- Reincarnation: Pythagoras promoted the theory that our souls never die, but rather go on to attach themselves to new forms after the physical body expires.

- Vegetarianism: Partly influenced by his belief in reincarnation, Pythagoras abstained from eating meat in an effort to do no harm to any creature that could be housing a formerly human soul.

- Acceptance of the impermanent nature of life: Life is in motion. The whole universe is constantly in flux, and only change itself is ultimately real. For this reason, Pythagoreans practiced non-attachment to the fleeting forms of life.

Pythagoras and his disciples worshiped the sun and the sun god, Apollo.

If you were born in a Western country, this person, and his philosophical legacy, has likely influenced you – whether consciously or subconsciously – on some level.

The Classical Period (~510 BC – 323 BC)

The Classical Period was much shorter than both the Archaic and Hellenistic. But in many ways, it’s the most Greek of the three periods of ancient Greece.

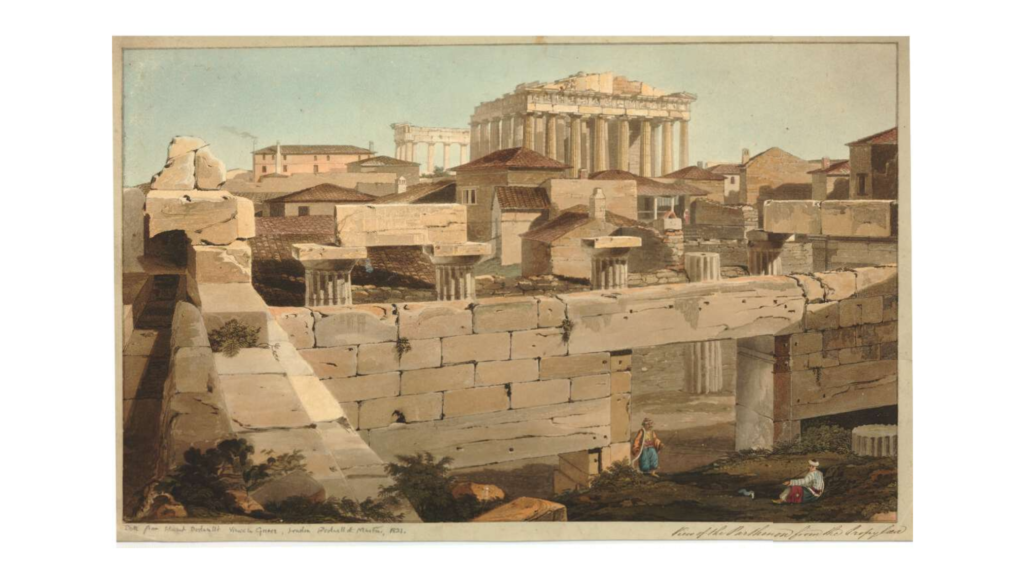

It was during these years that the world was gifted Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, the foundations of democracy, the Parthenon, and two new types of Greek columns: the Ionic and Corinthian Orders.

The Classical Period of Greece was bound on each end by two earth-shattering deaths — that of the last Athenian tyrant in 510 BC and Alexander the Great in 323.

The former death ushered in democracy, a renewed importance of the polis, or city-state, and a golden age of philosophy. The latter one introduced a long age of kings.

But in spite of so many incredible human achievements coming out of The Classical Period, it was largely marred by conflicts. Most notable among them is the Peloponnesian War — an epic showdown between Athens and Sparta that spanned almost three decades.

The Peloponnesian War

At the start of the Classical Period, the Athenians marshaled an alliance of Greek states, collectively called The Delian League, to liberate Persian-occupied Greek cities along the Ionian Coast of Asia Minor.

Their success in this endeavor lead to a period of Athenian naval dominance in the Aegean Sea.

But there was another league of Greek city-states that would eventually challenge the Athenians. It was the Peloponnesian League, which had the powerful city of Sparta at its helm.

With the external threat of the Persian Empire removed, tensions between these two leagues grew. Until, in 431 BC, conflict erupted when Sparta attacked Athens for violating the terms of a treaty.

This conflict would not resolve for 27 years. And, at its conclusion, Athens would be defeated by Sparta. And it would have its noble democracy forcefully replaced by thirty tyrants.

The History of the Peloponnesian War by the Classical Greek historian, Thucydides, details this conflict chronologically.

Democracy & The Athenian Golden Age

Prior to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, Athens enjoyed a long period of peace and prosperity known as The Athenian Golden Age.

For the first and only time throughout the three periods of ancient Greece, we see a new form of government called democracy take hold. And it was under the famed Athenian statesman, Pericles, that this was made possible.

Pericles expanded the privileges of the average Athenian citizen: Public officials were paid under his administration, thereby opening government to the middle class. These actions were probably an outgrowth of his attitude toward Athens and Athenians: That the city and its people were at the apex of Greek civilization.

I declare that our city as a whole is an education to Greece.

Pericles, Book 2, Chapter 6

He also significantly enriched the city by relocating the treasury of the Delian League — formerly located on the island of Delos — to Athens. He repaired the Parthenon and other structures that had been damaged during the Greco-Persian Wars with funds from this treasury.

The openness and prosperity of Athens during this golden age allowed for art and philosophy to flourish.

And Socrates, a seminal figure in Western Philosophy, became active during this time.

Famous Greeks from The Classical Period: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle

The big three ancient Greek philosophers — Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle — all came out of the Classical Period of ancient Greece. And each was influenced by the prior one.

Socrates, the OG, was born nearby Athens in 470 BC. He spent the majority of his life in that city. And he was active during the years of the Athenian Golden Age and The Peloponnesian War.

Plato, born in 428 to Athenian nobles, was his disciple. We have Plato to thank for carrying on the legacy of Socrates. One of his crowning achievements, in addition to writing numerous dialogues, was creating The Academy at Athens. This institution taught people how to think like Socrates.

One of The Academy’s most famous students was Aristotle. Aristotle was a polymath, meaning he was an expert in many different domains. But he’s best known for his political and metaphysical philosophy. His famous works, such as Politics and Nicomachean Ethics, are still extant and read widely.

Around 366, he left his homeland of Macedonia, a growing power in northern Greece, and moved to Athens to study. He trained at The Academy under a very elderly Plato and remained there until Plato’s death in 347.

When he returned to Macedonia, Aristotle became the tutor of a young prince of the Argead dynasty who would grow up to be Alexander the Great. His tutorship of Alexander is relevant for several reasons. In his very short life, the young prince achieved hitherto unknown conquests. Alexander brought the spirit of ancient Greece to the entire world — as far south as Upper Egypt and as far east as the Indus River. In a romantic sense, he was the culmination of the entire Classical Period in one person.

But his death kindled a whole new era, which would be the last and most illustrious of the three periods of ancient Greece: The Hellenistic Period.

The Hellenistic Period (~323 BC – 31 BC)

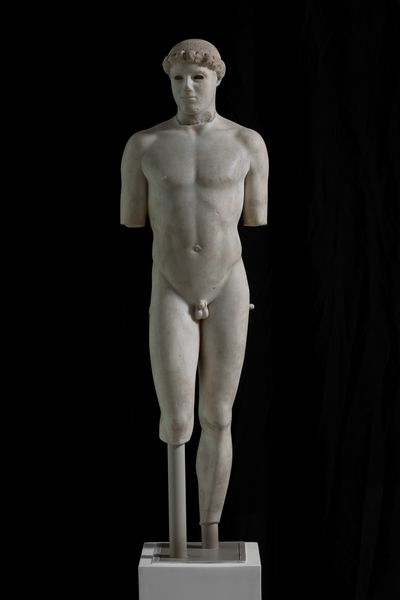

During the Hellenistic Period, the last of the three periods of ancient Greece, we see shifts in politics, art, culture, and the role of women.

In politics, the importance of individual city-states dwindled as they were annexed into Alexander the Great’s empire, and later on into the kingdoms of his successors. For this reason, the Hellenistic Period is sometimes called an Age of Kings.

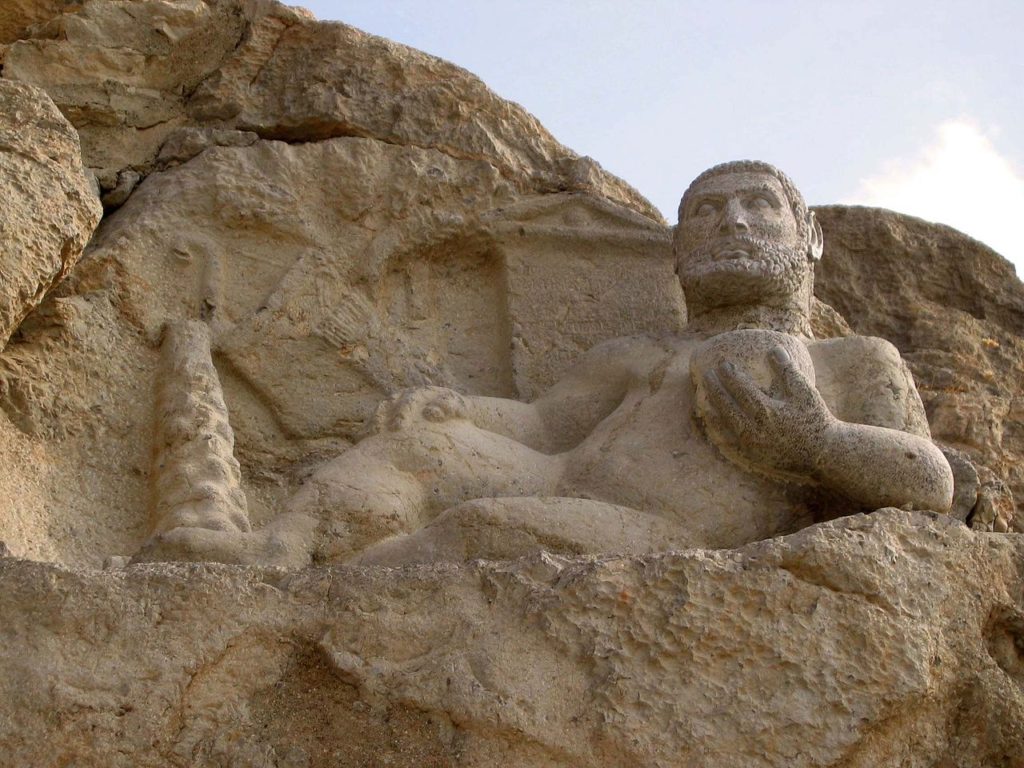

In Hellenistic art and sculpture, we see a focus on beauty and precision in depictions of the human form. This was achieved through showing realistic anatomy, ornate details, and movement that accentuated forms. Drama, sensuality, and eroticism are also new themes in Greek sculpture. And we see a marked increase in representations of the female nude. There is also an explosion in the production of luxury items, particularly jewelry.

In Hellenistic culture, we see a blending of the Greek identity with foreign ones. Hellenization, the passing of Greek language, art, and customs to non-Greek peoples, was a theme throughout the entirety of Alexander’s empire. But, on the flip side, Greek settlers in these new lands often adopted the culture and customs of natives too. This is most evident in Ptolemaic Egypt. Here we see the rise of syncretized gods, or those that were combinations of both ancient Greek and Egyptian gods. Serapis, a combination of Zeus and Osiris, is perhaps the most famous one.

Finally, we see an expansion of the roles of Greek women, particularly from the upper classes, during the Hellenistic Period. The prominent role of aristocratic women, such as Olympias, Alexander the Great’s mother, and Cleopatra VII, the final Hellenistic queen of Egypt, can’t be ignored. Contrast this with the Archaic and Classical periods, which afforded women zero visibility or role outside of the home.

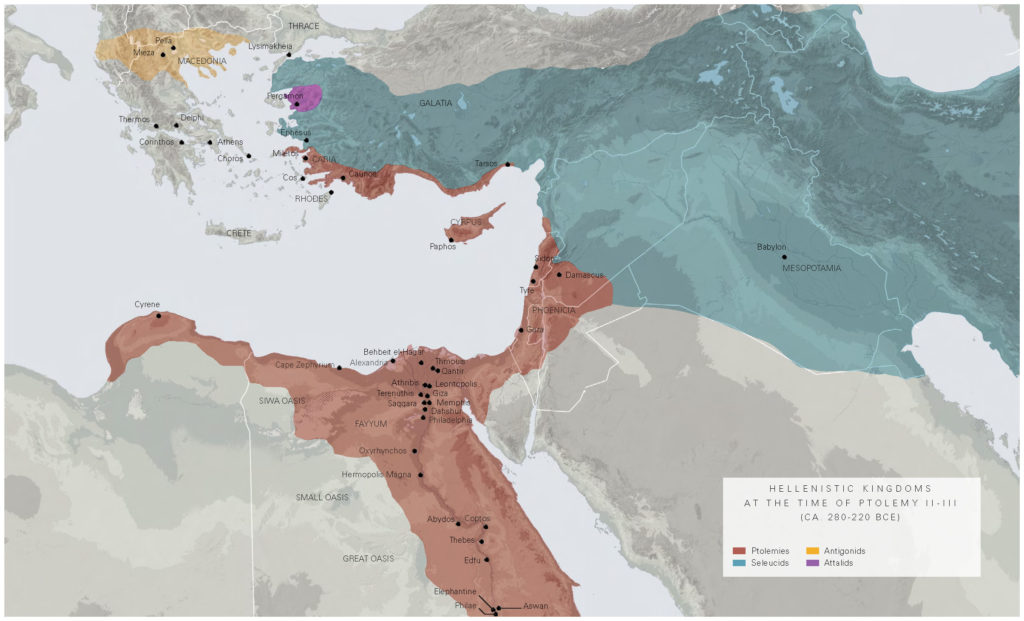

Age of Kings: Dividing Alexander’s Empire

By the time of Alexander the Great’s untimely death in 323 BC, he’d strung together the largest empire in human history. It included all of Greece, Cyrenaica in modern-day Libya, Egypt, Anatolia, the Levant, and a huge swath of Western Asia, terminating at the Indus River valley in modern-day Pakistan.

Alexander believed that unity was humanity’s highest ideal. And his relentless conquests aimed to fulfill that ideal by uniting the whole world under one Hellenistic flag.

But his death produced the opposite effect. Alexander’s successors, a group of generals collectively called the Diadochoi, warred for control of his vast empire. This resulted in his territory being divided several ways.

Hellenistic Successor Kingdoms

Initially, Alexander’s empire was split between five of his generals.

But we’ll only focus on two of these dynasties here, the ones that prevailed throughout most of the Hellenistic Period: The Ptolemies in Egypt and Cyrenaica and the Seleucids in Asia.

Each Hellenistic kingdom was distinct from the others in many ways — culturally, politically, artistically, etc. But Hellenistic kingship shared some universal characteristics. Most notably, Hellenistic monarchs ruled with an air of drama and theater. They often tried to maintain the illusion of democracy in Greek cities. And it wasn’t uncommon for cults of personality to arise around them both in life and after death. They also each engaged in a practice called royal eugeretism. Hellenistic kings would bestow benefactions on cities within their empires in exchange for godlike honors, and other intangible privileges, on behalf of the citizens.

The Ptolemies

Ptolemy I Soter, a former general in the army of Alexander the Great, crowned himself pharaoh of Egypt in 305 BC. His family would go on to govern that country for the next 300 years.

Ptolemy ruled from Alexander’s eponymous city, Alexandria, which would quickly become the most important capital in the Hellenistic world. One of the reasons for this is that it was extremely diverse. There were immigrant populations of Jews and, of course, Greeks who lived amongst one another with native Egyptians too. And, as a major port and trading hub, foreigners from all over the Mediterranean would spill into Alexandria everyday.

Alexandria: Intellectual Capital of the Hellenistic World

Ptolemaic Alexandria was a place of great wealth and beauty, as well as a hotbed for scientific and philosophical advancement. The Ptolemies built institutions like the “Mouseion,” meaning Temple of the Muses, where scholars from around the world would flock to expand their learning. One of the structures attached to the Mouseion was the famed Library of Alexandria.

Figures like Euclid, who achieved major advancements in geometry, flourished in Alexandria. Stoicism, a new school of philosophy, also became wildly popular in this city.

The Ptolemies were remote from everyday Egyptians. In fact, none of them except Cleopatra VII even spoke the language of the natives. But they managed to honor them by worshipping the ancient Egyptian gods. Many of the extant temples in Egypt dedicated to the Egyptian pantheon were constructed by members of the Ptolemaic dynasty. These include the Temple of Philae, dedicated to the mother goddess Isis, the Temple of Edfu, dedicated to the falcon god Horus, and the Temple of Kom Ombo, dedicated to the crocodile god Sobek.

On a personal level, the Ptolemies engaged in some strange behavior — at least by Greek standards. They quickly adopted Egyptian customs that would have been regarded with distaste in their native Macedonia. For example, sibling marriage was a prominent feature of the Ptolemaic dynasty as early as its second generation.

Arsinoë II was the first Ptolemaic queen to be married to her full-blooded brother. And Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemaic dynasts, was heavily inbred by the time of her rule eight generations later.

Fun fact: Arsinoë II was worshipped as a goddess in Egypt after her death.

The Seleucids

The Seleucids are sometimes called the Elephant Kings because, at the very beginning of the Hellenistic Period, a king from India gifted Seleucus I Nicator (the father of the Seleucid dynasty) 500 war elephants.

These elephants aided the Seleucids in winning several decisive battles. The result was that, for a majority of the Hellenistic Period, they ruled all of Asia. Their territory included the ancestral lands of Persia, Babylonia, and Syria.

At first the Seleucid Empire was based out of the ancient city of Babylon in Mesopotamia. But later generations moved its capital to Antioch in Syria.

Because their empire was so large — the largest of all the Hellenistic kingdoms, in fact — Seleucid monarchs were always on the move. They’ve been branded as “itinerant kings,” by one Hellenistic historian, Paul J. Kosmin.

Whereas the royal court of the Ptolemies was firmly rooted in Alexandria, that of the Seleucids would move freely with its traveling kings.

Seleucid power was centralized in the person of the monarch. And unlike the Ptolemies, who were rather isolated, Seleucid monarchs made great efforts to interact with their subjects.

Another feature of Seleucid kingship was city planning and building. They were prolific city builders and master architects.

Dynastic struggles plagued the Seleucids from 161 BC onward. And in 63 BC, the empire dissolved at the hands of the Roman Republic.

Rise of the Roman Republic

As early as the Classical Period, the fledgling Roman Republic was contending with the Carthaginian Empire in the western Mediterranean. But after its decisive defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War, Rome became the de facto world power.

And it quickly set its sights due east toward the troubled Hellenistic kingdoms.

At around 217 BC, the Roman Republic became a major player in the affairs of the eastern Mediterranean. And in 215, the first direct conflict between a Hellenistic state and Rome occurs.

One by one, each of the kingdoms fell and was annexed into Rome’s growing territory. The Ptolemies were the last of the Hellenistic dynasties to survive. And it was thanks Cleopatra’s savvy governance that they did for so long.

Cleopatra used her sexuality as a diplomatic tool. To that extent, she gave birth to four children between two different Roman statesmen. Each of these was strategic and bought Egypt several decades as a semi-autonomous client state of Rome long after the other Hellenistic states fell. But luck ultimately failed her and her children too.

The Battle of Actium, a showdown in 31 BC between the Ptolemaic forces of Cleopatra and the Romans, led by Gaius Octavius, spelled the end of her dynasty.

Afterward, Cleopatra returned to Alexandria where she suicided. This is the event that most historians agree on as the definitive end of the Hellenistic Period. But the Ptolemaic threat had not been completely subdued with her children roaming freely. Octavius, now Caesar Augustus, Roman emperor, had Caesarion murdered and her other three children enslaved.

These events close the chapter on the three periods of ancient Greece. Despite Hellenistic art and culture remaining alive under the Roman Empire for quite a while, the Hellenistic Period, and the epoch of ancient Greece more generally, was over.

Its beautiful material legacy, however, was still visible all around the eastern Mediterranean. And today remnants of the Hellenistic Period can be seen in the premier museums and cultural institutions of the world.