The Trojan War is one of those rare events that’s equal parts myth and history. In fact, until the 19th century, it was regarded solely as a fable out of ancient Greek mythology. But developments from the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann proved otherwise.

The German archaeologist unearthed a settlement, Hisarlik, on the site where ancient historians believed Homer’s Troy to be. And some context layers of that site show evidence of a major conflict.

Since these findings, historians and classicists have come to agree that the Trojan War did, in fact, occur at least in some capacity – although perhaps not exactly Homer’s mythological version of it.

Homer’s Trojan War: The Iliad

We’d probably know nothing about Troy if it weren’t for Homer.

The famous blind poet lived in Greece somewhere around the 9th century BC – assuming he ever actually lived at all. And he’s credited for two epic poems that center around the Trojan War and its aftermath: the Iliad and the Odyssey. The former is the story of the Trojan War itself, a ten-year conflict that took place outside the high walls of Troy. It started after a certain Trojan prince, Paris, stole Helen, the face that launched 1,000 ships and the wife of the Spartan king, Menelaus, from her homeland. And it culminated in the destruction of Troy by a host of Greek tribes, collectively referred to as the Achaeans, under the leadership of the great king, Agamemnon.

Even to Homer the Trojan War would have been ancient history, taking place hundreds of years before his lifetime. And by the epoch of Alexander the Great, who was as far removed from the Trojan War as modern people are from the Crusades, it was all but mythology.

So it should be clear that from its origins Homer’s Trojan War was by no means a report of historic events. Rather it’s a fable that’s as much about the feuds and alliances of Greek gods as it is about a clash of men. The Trojan War also represents a clash of civilizations – the East versus the West – on a symbolic level.

But it’s not until the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann in the late 1800s that we start to get a picture of what may have actually happened at this site.

Schliemann’s Trojan War: The Archaeological Record

Heinrich Schleimann was a German archaeologist who made some of the most important discoveries in Trojan War history.

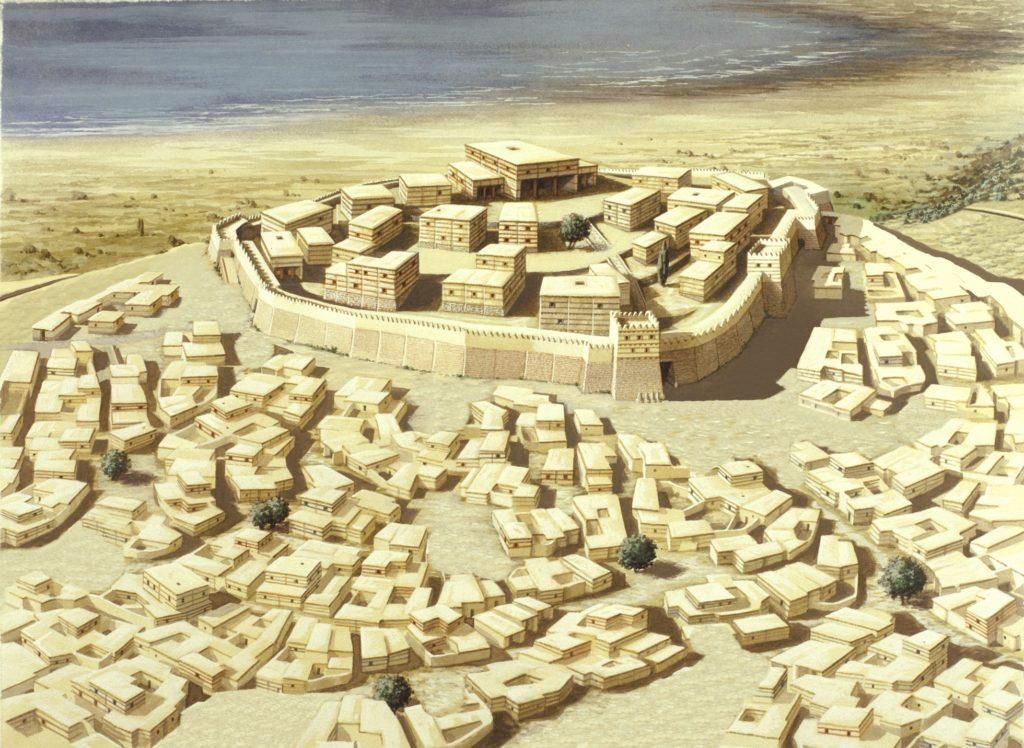

In 1871, he traveled to the site of ancient Troy, in modern-day Turkey. Using carefully calibrated tools, he began to excavate the ruins of the city. And, to his amazement, he found evidence of a massive siege that had taken place there thousands of years earlier. He also found evidence of a huge fire that had destroyed the city.

These findings supported the historical account of the Trojan War, which had previously been considered a myth. In addition to his archaeological discoveries, Schliemann also found numerous artifacts, including weapons, pottery, and jewelry. These artifacts are now on display in museums around the world. Thanks to Schliemann‘s excavations, we now have a better understanding of the Trojan War and the civilization that was destroyed by it.

However, it should be noted that much of his work was destructive to the site itself. And by modern archaeological standards, Schliemann and his team deserve their fair share of criticism.

Troy’s Archaeological Context Layers

Since Schliemann‘s work at Hisarlik, many distinct context layers of the archaeological site at Troy have been uncovered. The record shows that there were several independent settlements built there one on top of the other over time.

And on more than one occasion the settlements were either destroyed or abandoned.

However, the particular settlements or context layers associated with Homeric Troy are Troy VI and VII. These settlements show signs of a conflict, resulting in a massive conflagration, around 1180 BC. And this is, from an historical and archaeological perspective, what we call the Trojan War.

What Actually Happened At Troy?

So what actually happened at Troy?

The short answer is that we don’t know for certain.

However, the destruction dates of the context layers that are associated with the Trojan War – that is, VI and VII – coincide with the period of ancient Mediterranean history known as the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

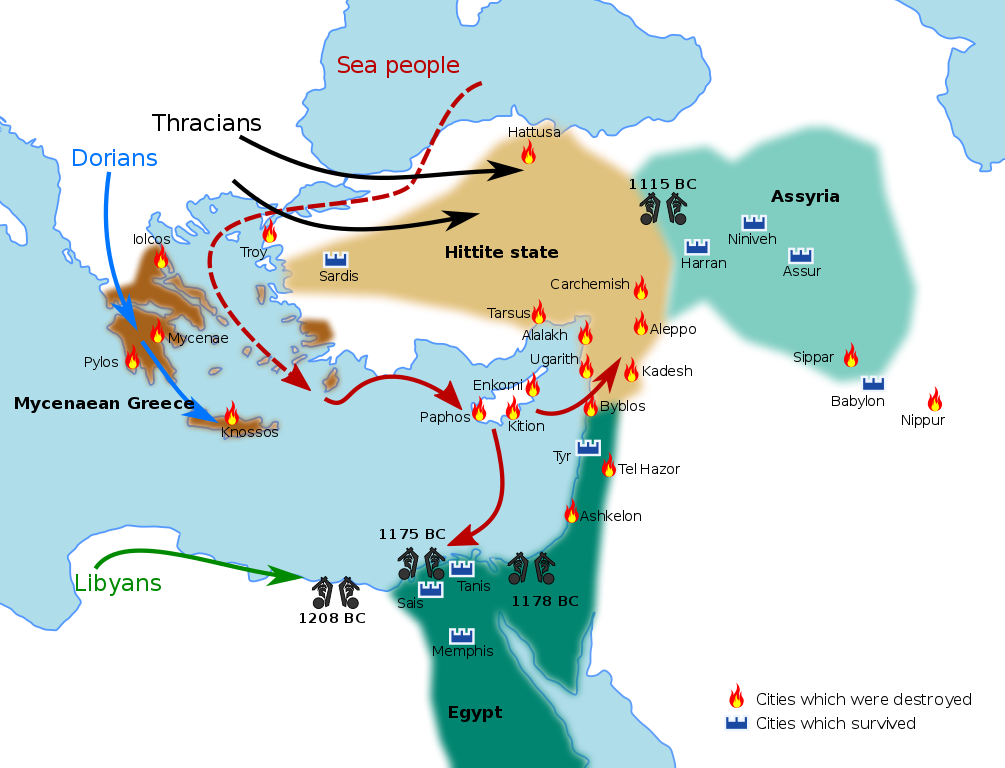

Archaeologists have documented widespread upheaval in the eastern Mediterranean during this period. The culpability for this upheaval has been laid at the feet of the so-called “Sea Peoples.” Exactly who they are or what motivated them is less clear. But the Sea Peoples are a name we’ve given to a federation of marauding warriors from the Northern Aegean, or perhaps the Black Sea.

This gang of tribes swept into the Mediterranean around 1200 BC and smashed several of the prominent civilizations that had ruled there. Notably, the Mycenaean Greeks were wiped out by the Sea Peoples. The Egyptians, under the rule of Ramesses III, only narrowly defeated the intruders. But their incursion into that country catalyzed the long decline of Pharaonic Egypt. And in Anatolia, the landmass that the city of Troy lay on, the Hittite Empire was all but decimated.

So one plausible explanation for the historic Trojan War was that the settlement called Troy VI and Troy VII fell to the Sea Peoples during the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

And, perhaps, Homer reshaped this event as an epic face-off between east and west, Trojans versus Greeks.

But who were the Trojans?

Who Were the Trojans?

We’ve established a mythical and historical basis for the Trojan War. But what do we mean by Trojan from both of those perspectives?

And if Troy was located in Anatolia at the time of the Hittite Empire, then doesn’t that mean the Trojans were Hittites?

Not exactly.

The people who inhabited Troy VI and VII were certainly in league with the Hittites. But they appear to have had their own distinct civilization. At the beginning of the Iliad, it’s noted that the Trojans called on the Carians, Phrygians, and other ancient Anatolian cultural and ethnic groups to marshal with them against the invading Achaeans. This supports the theory that they were each distinct from one another and separate from the Hittite Empire altogether.

Then were they Greeks?

No, not quite.

The language that the Trojans spoke is unknown, but we know it wasn’t Greek. Many researchers believe it was Luwian, which was a language that was widely used in Anatolia during the Bronze Age.

Additionally, Trojan characters were often represented as distinctly eastern, or non-Greek, in art and sculpture. From ancient sculpture to modern paintings, Paris, a Trojan prince and one of the main characters in Homer’s Iliad, is often depicted wearing a Phrygian cap. The Phrygian cap came to represent an emblem of the East. It communicated that the wearer was from a non-Greek culture located somewhere in the Near East. A distinctly Greek character, such as Achilles or Menelaus, for example, would never be shown wearing a Phrygian cap.

So while the Trojans certainly weren’t Greek, they were, at the very least, acquainted with the broader Greek world. For now, all we can say with certainty is that they were a distinct cultural group located in northwestern Anatolia with significant links to the ancient Greek world.