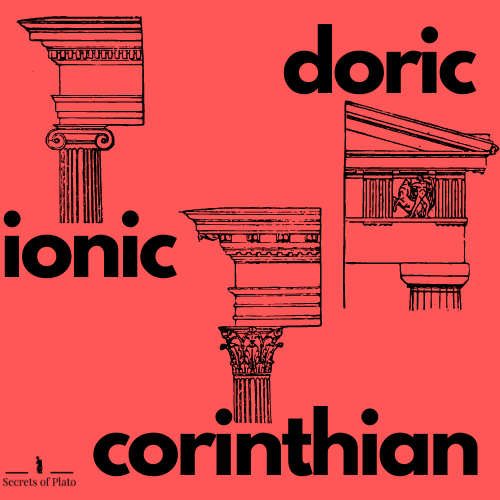

There are three types of Greek columns that correspond to the Classical Orders of Architecture: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. And each type is still used in modern architectural design. If you take a closer look at your local civic buildings, churches, and museums, you’ll notice it.

That’s because the ancient Greeks influenced our culture with more than just their ideas. And that can be applied to pretty much every civilization that came after them – not just ours. The Romans, for example, were dazzled by ancient Greek architecture. They used Greek models as the blueprints for their own buildings, and went on to contribute two original types of columns to the Classical Orders of Architecture.

Today, famous designs inspired by ancient Greek architecture can be found all over the world. The Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg, Russia, the British Museum, and the New York Stock Exchange are just a few examples. Their different types of Greek columns are the most identifiable features of these Grecian-style designs, which also serve as a practical guide to better understanding them.

In this article, we’ll review what the three types of Greek columns are and how to identify them.

Types of Greek Columns

The Doric and Ionic types of Greek columns have their roots in the Archaic Period of ancient Greece – long before Socrates and Plato walked the earth. Corinthian columns came later. Their origins have been traced to the Late Classical Period.

All three types were developed at the outset to be used for temple buildings. And, in effect, they’re a decorative approach to a prehistoric construction style called post-and-lintel systems.

These are defined by the construction of vertical pieces, called posts, that support horizontal pieces, called lintels. Post-and-lintel systems are as old as time: think Stonehenge and the oldest Egyptian temples. And they’ve been used in both the east and west alike.

They’re distinct in ancient Greek architecture, however, because, instead of simple posts, the Greeks used elaborate columns. Rather than taking a solely functional approach to these vertical support pieces, the Greeks made them intricate and beautiful. And, thus, the three types of Greek columns were born.

So, how do Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns differ from one another?

Doric Columns

Doric columns are the simplest of the three types of Greek columns in the Classical Orders of Architecture.

For reference, the remains of the Temple of Apollo at Corinth has a well-preserved row of Doric columns – ironically, not Corinthian. Their origins can be traced back to around 560 BC. The Parthenon also showcases a classic example of Doric columns, which subscribe to an all-encompassing Doric Order.

The Order governs all architectural elements of a Doric temple, such as its pediment, frieze, and entablature. In this article, however, we’ll only focus on the Doric Order as it relates to columns, which are each composed of a capital, a shaft, and a base.

Let’s start with the capital, the uppermost part of the column. The Doric capital is characterized by a simple flare attached to a slab. The slab is the piece that connects the column to the entablature.

Below the capital is the shaft, which most non-art historians often mistake for the entire column itself. The shafts of Doric columns have shallow flutes, or grooves, along their surfaces. From a distance, these look like ridges or lines.

Now, onto the final piece of the column: the base. Or, in the case of the Doric column, its lack thereof.

Of the three types of Greek columns, Doric are unique in that they don’t have bases. The fluted shaft of a Doric column is supposed to make direct contact with the temple floor without being interposed by a base.

Entasis: The unique shape of Doric columns

The final important feature of a Doric column relates to the width and shape of its shaft.

At its highest point, nearest to the capital, the Doric shaft is at its narrowest. It then becomes progressively wider toward the middle-bottom area. That is, until it reaches about a third of the way down, which is where the shaft is at its widest. Then it tapers off, becoming progressively narrower again toward the bottom of the shaft.

This is called entasis, i.e. the swelling of the body of a column. Its purpose is debated. But many architectural experts and art historians agree that it was largely aesthetic in nature.

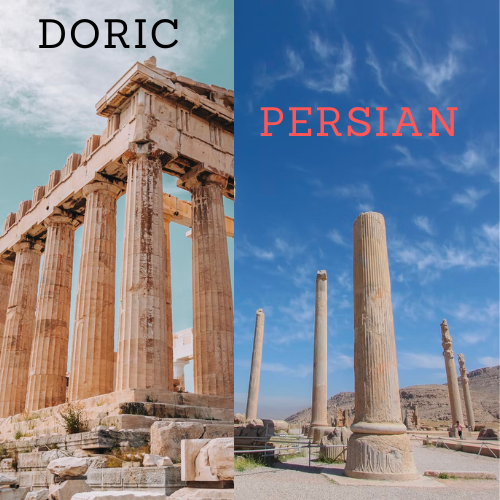

You can really see it when you contrast Doric designs with other columns from the same period, such as the ones engineered by the Achaemenid Persians at Persepolis. Notice how the Persian columns are pin straight, whereas Doric columns have more intricate shaft proportions.

So, now you know the elements of Doric columns. But it’s important to note that their design wasn’t random. The massive amount of money and craftsmanship required to engineer them begs the question: What did these archaic Greek columns signify to their makers?

Vitruvius, the famed Roman architect, relates them to the power of the masculine form in de Architectura, Book IV, especially as they contrast with their more elegant successors.

The wide, imposing nature of Doric columns was perhaps an attempt on the part of the ancient Greeks to represent strength and masculinity.

The same, however, can’t be said for our next type of Greek column.

Ionic Columns

Not long after the Doric, a new order emerges: the Ionic Order.

And our second type of Greek column, the Ionic column, comes out of this order.

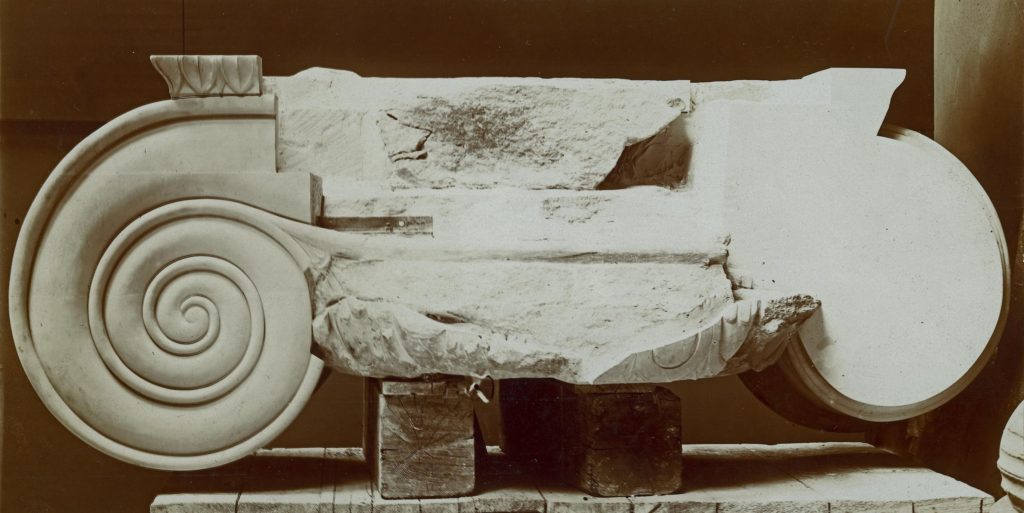

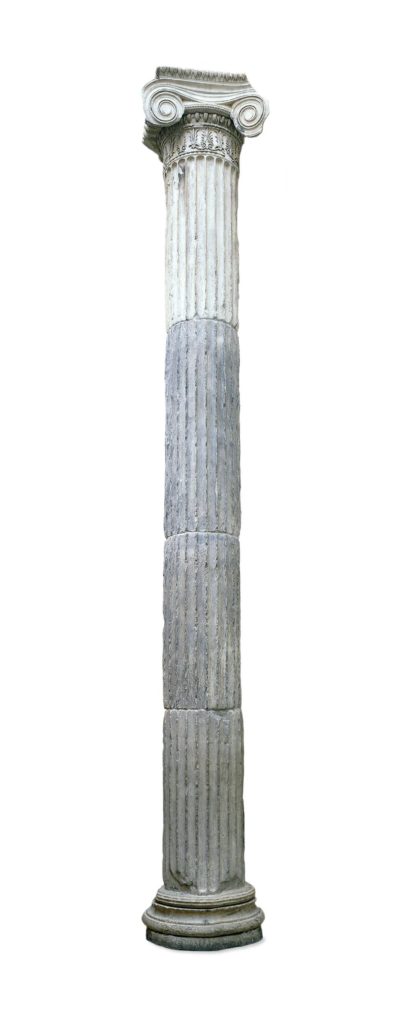

Whereas the Doric column is wide and imposing, the Ionic column is tall, thin, and elegant. Its most recognizable quality is its capital, which has two distinct swirling features called volutes.

Additionally, the fluted shaft of the Ionic column lacks entasis, which is present in Doric columns. It also, notably, has a base.

The extant columns of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis in Athens are classic examples of the Ionic Order. Built in 421 BC, during the Athenian Golden Age, the Erechtheion served as a temple for the cult worship of the goddess Athena.

The elegance and intricacy of Ionic columns is clear, especially when in contrast to the Doric Order.

But the ancient Greeks didn’t stop at that. With our next type of Greek column, we’ll see just how elaborate they can get.

Corinthian Columns

The third and final ancient Greek contribution to the Classical Orders of Architecture are Corinthian columns. These get their name from a myth about a Corinthian girl who died tragically, and an acanthus plant that sprouted from her grave.

Corinthian columns are also distinguished by their capitals, which, as you can see, are extremely ornate.

With Corinthian columns, floral and leaf-like elements adorn the capitals, giving them an air of opulence and grandiosity. These are meant to resemble the leaves from the Corinthian myth of the acanthus plant, which is endemic to the Mediterranean Basin.

In addition to floral elements, Corinthian columns have volutes protruding from each of their sides. Although these are often smaller and less visible than their Ionic counterparts.

Corinthian columns are usually tall and slender with fluted shafts that lack entasis. They have bases as well.

However, the decorative elegance of Corinthian columns far surpasses that of both the earlier orders of ancient Greek architecture.

The Legacy of Ancient Greek Architecture

The ancient Greeks gifted to the world three enduring types of Greek columns.

Unfortunately, they didn’t have time to imagine up any more. The Greek peninsula was conquered by the Roman Republic in 146 BC, which passed the proverbial baton of the Greek architectural imagination to the Romans.

So inspiring was ancient Greek architecture, however, that the Romans went on to add two more types of columns to the Classical Orders of Architecture – Composite and Tuscan.

In architecture, like with everything else, the ancient Greeks were called to work with precision in pursuit of the apex of aesthetic beauty. And this is visible in their material legacy.